Overview

Chemical reactions often occur in a stepwise fashion, involving two or more distinct reactions taking place in a sequence. A balanced equation indicates the reacting species and the product species, but it reveals no details about how the reaction occurs at the molecular level. The reaction mechanism (or reaction path) provides details regarding the precise, step-by-step process by which a reaction occurs.

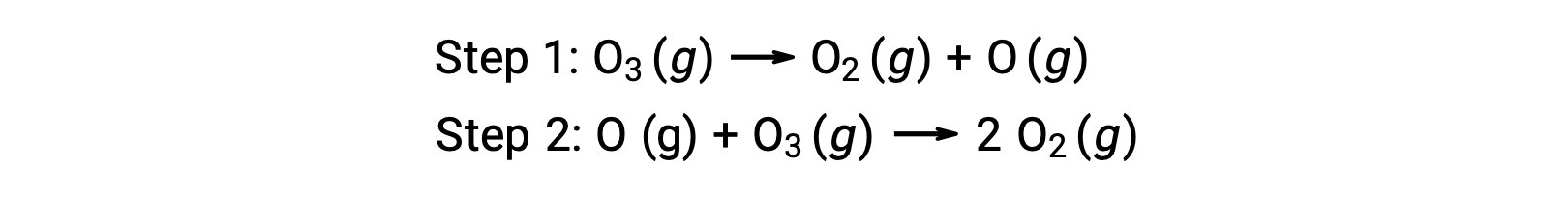

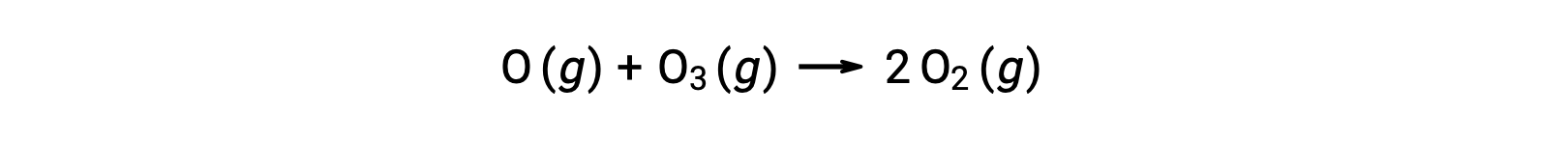

For instance, the decomposition of ozone appears to follow a mechanism with two steps:

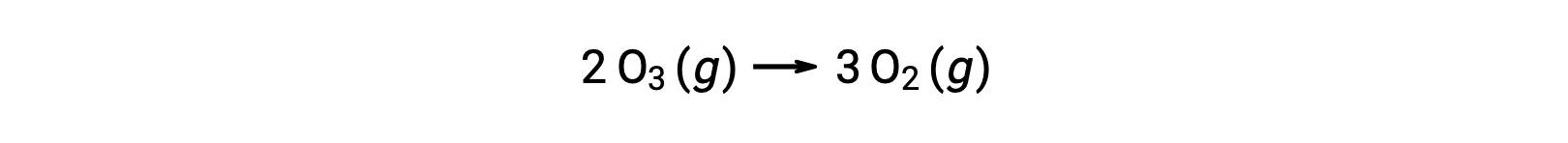

Each of the steps in a reaction mechanism is called an elementary reaction. These elementary reactions occur in sequence, as represented in the step equations, and they sum to yield the balanced chemical equation describing the overall reaction:

Notice that the oxygen atom produced in the first step is consumed during the second and does not appear as a product in the overall reaction. Such species that are produced in one step and consumed in a subsequent one are called reaction intermediates.

While the overall reaction equation indicates that two ozone molecules react to give three oxygen molecules, the actual reaction mechanism does not involve the direct collision and reaction of two ozone molecules. Instead, one O3 decomposes to yield O2 and an oxygen atom, and a second O3 molecule subsequently reacts with the oxygen atom to yield two additional O2 molecules.

Unlike balanced equations representing an overall reaction, the equations for elementary reactions are explicit representations of the chemical change. An elementary reaction-equation depicts the actual reactant(s) undergoing bond-breaking/making, and the product(s) formed. Thus, the rate law for an elementary reaction may be derived directly from its balanced chemical equation. However, this is not the case for typical chemical reactions, for which rate laws may be reliably determined only via experimentation.

Unimolecular Elementary Reactions

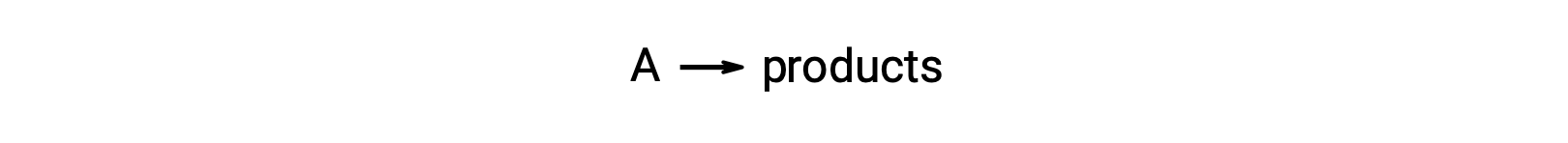

The molecularity of an elementary reaction is the number of reactant species (atoms, molecules, or ions). For example, a unimolecular reaction involves the reaction of a single reactant to produce one or more molecules of product:

The rate law for a unimolecular reaction is first order; rate = k [A].

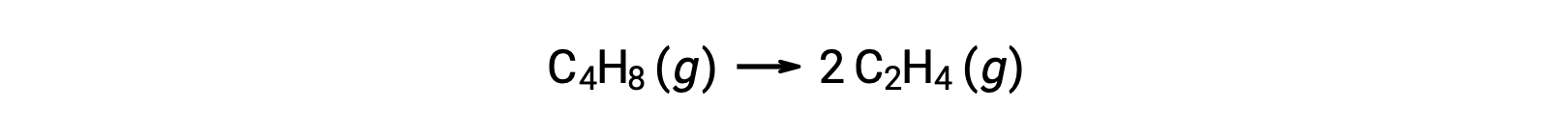

A unimolecular reaction may be one of several elementary reactions in a complex reaction mechanism. For instance, the reaction (O3 (g) → O2 (g) + O) illustrates a unimolecular elementary reaction occurring as a part of a two-step reaction mechanism. However, some unimolecular reactions may be the only step of a single-step reaction mechanism. (In other words, an “overall” reaction may also be an elementary reaction in some cases.) For example, the gas-phase decomposition of cyclobutane, C4H8, to ethylene, C2H4, is represented by the chemical equation:

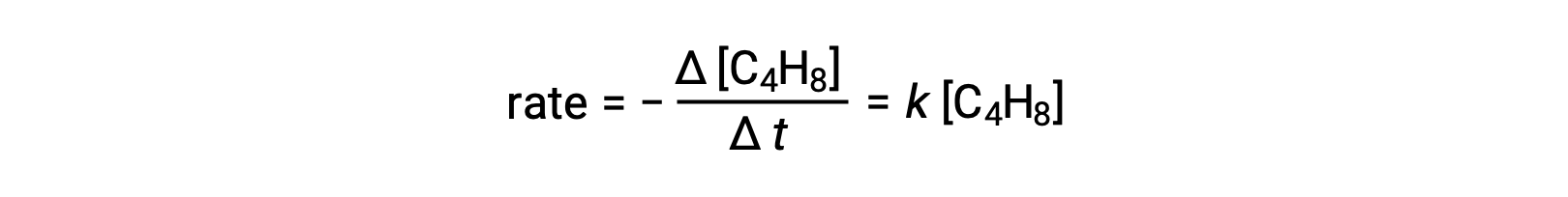

This equation represents the overall reaction, describing a unimolecular elementary process. The rate law predicted from this equation, assuming it is an elementary reaction, turns out to be the same as the rate law derived experimentally for the overall reaction, showing first-order behavior:

This agreement between observed and predicted rate laws indicates that the proposed unimolecular, single-step process is a reasonable mechanism for the butadiene reaction.

Bimolecular Elementary Reactions

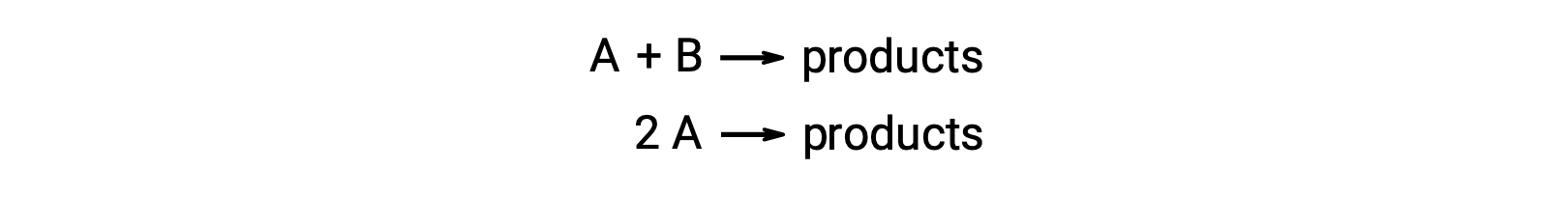

A bimolecular reaction involves two reactant species. For example:

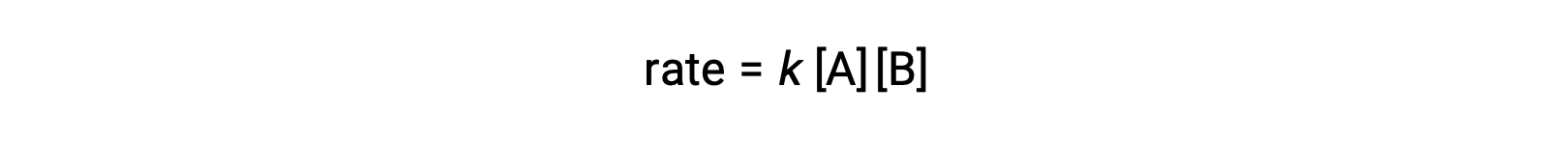

In the first type, where the two reactant molecules are different, the rate law is first-order in A and first order in B (second-order overall)

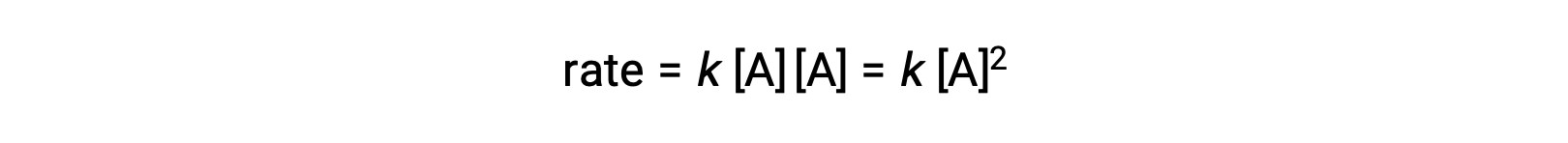

In the second type, in which two identical molecules collide and react, the rate law is second order in A:

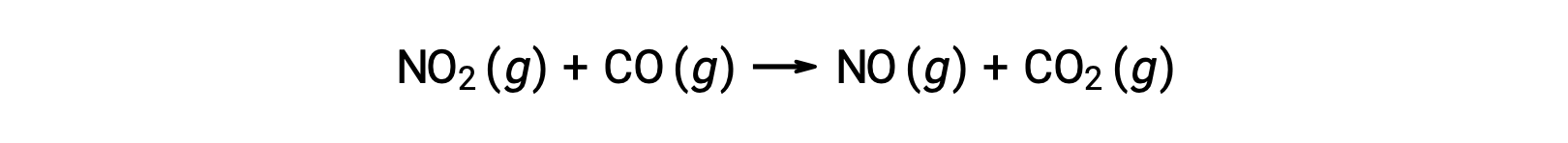

Some chemical reactions occur by mechanisms that consist of a single bimolecular elementary reaction. One example is the reaction of nitrogen dioxide with carbon monoxide:

Bimolecular elementary reactions may also be involved as steps in a multistep reaction mechanism. The reaction of atomic oxygen with ozone is the second step of a two-step ozone decomposition mechanism:

Termolecular Elementary Reactions

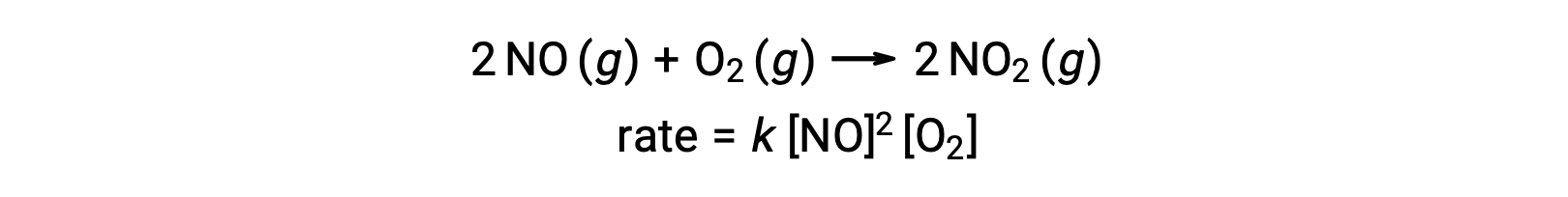

An elementary termolecular reaction involves the simultaneous collision of three atoms, molecules, or ions. Termolecular elementary reactions are uncommon because the probability of three particles colliding simultaneously is very rare. There are, however, a few established termolecular elementary reactions. The reaction of nitric oxide with oxygen appears to involve termolecular steps:

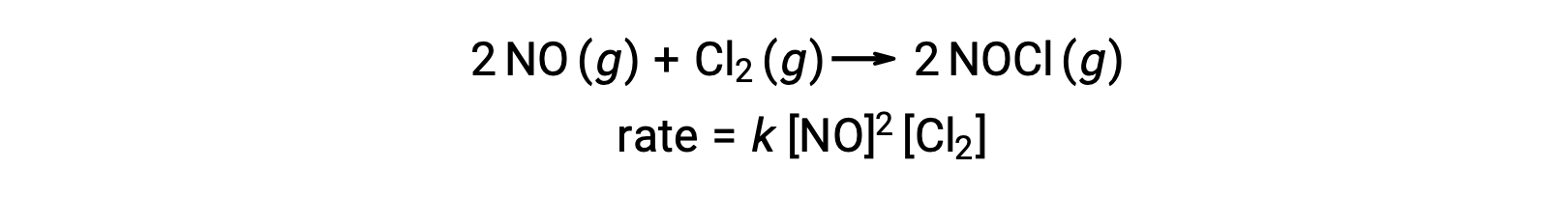

Likewise, the reaction of nitric oxide with chlorine appears to involve termolecular steps:

Often one of the elementary steps in a multistep reaction mechanism is significantly slower than the others. Because a reaction cannot proceed faster than its slowest step, this step will limit the rate at which the overall reaction occurs. The slowest elementary step is therefore called the rate-limiting step (or rate-determining step) of the reaction.

This text is adapted from Openstax, Chemistry 2e, 12.6: Reaction Mechanisms.

Procedure

A chemical reaction is often represented by an overall balanced chemical equation indicating the reactants and products.

However, the actual reaction is often more complex and transpires in multiple steps. For instance, this reaction of nitric oxide with hydrogen forming nitrogen gas and water takes place in three distinct, successive steps. These steps are called the reaction mechanism.

Each step in the reaction mechanism is called an elementary reaction and represents the interaction, such as bond breakage or formation, between the reacting species.

Specific molecules, like dinitrogen dioxide and nitrous oxide, are formed during one elementary step and consumed during another. Such species are called reaction intermediates.

Reaction intermediates are low-energy products of an elementary reaction. They are often short-lived, which explains their absence in the product mixture. Reaction intermediates are not the same as activated complexes. Activated complexes are high-energy transition states existing only during the transformation of reactants to products.

Combining the elementary steps gives the equation for the overall chemical reaction. Here, the reaction intermediates are eliminated and hence do not appear in the overall chemical equation.

The different elementary reactions may progress at varying speeds. The slowest elementary step determines the overall reaction rate. Here, the reaction of dinitrogen dioxide with hydrogen gas is the rate-limiting step.

Elementary reactions can be commonly characterized as three types, depending on the number of reacting molecules or molecularity.

In a unimolecular reaction, a single reactant molecule transforms into one or more products. In a bimolecular reaction, two distinct molecules react. A termolecular reaction, though very rare, involves three individual molecules reacting to yield intermediates or products.

Unlike the rate law for an overall chemical reaction, which is determined experimentally, rate laws for elementary reactions can be predicted from stoichiometric coefficients of their reactants. In short, the molecularity of an elementary reaction corresponds to the overall reaction order of the elementary step.

Hence, unimolecular reactions are often first-order reactions, bimolecular reactions are second-order, and termolecular reactions are of the third order.

An understanding of reaction mechanisms and kinetics helps chemists in identifying and optimizing chemical reactions.