Overview

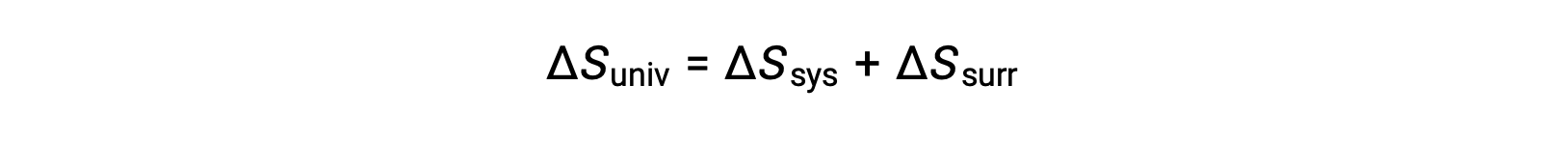

In the quest to identify a property that may reliably predict the spontaneity of a process, a promising candidate has been identified: entropy. Processes that involve an increase in entropy of the system (ΔS > 0) are very often spontaneous; however, examples to the contrary are plentiful. By expanding consideration of entropy changes to include the surroundings, a significant conclusion regarding the relation between this property and spontaneity may be reached. In thermodynamic models, the system and surroundings comprise everything, that is, the universe, and so the following is true:

To illustrate this relation, consider again the process of heat flow between two objects, one identified as the system and the other as the surroundings. There are three possibilities for such a process:

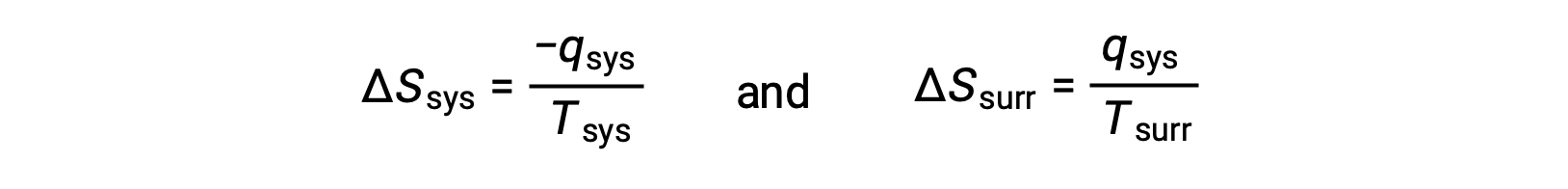

- The objects are at different temperatures, and heat flows from the hotter to the cooler object. This is always observed to occur spontaneously. Designating the hotter object as the system and invoking the definition of entropy yields the following:

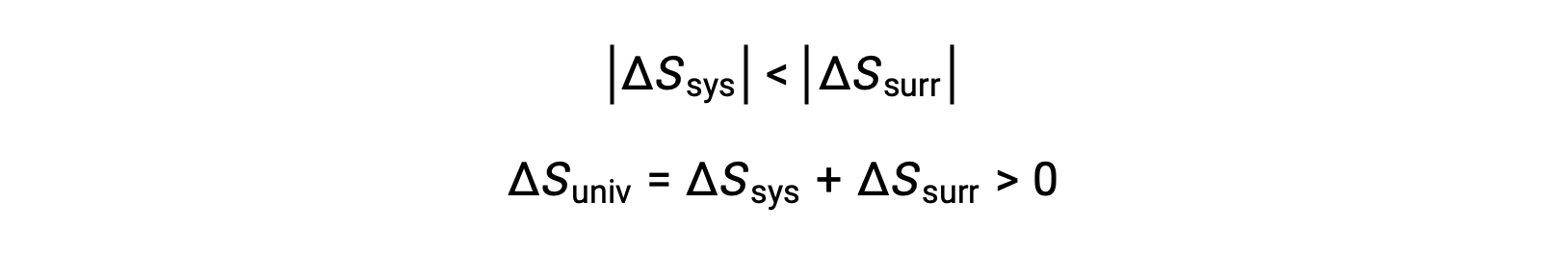

The magnitudes of −qsys and qsys are equal, their opposite arithmetic signs denoting loss of heat by the system and gain of heat by the surroundings. Since Tsys > Tsurr in this scenario, the entropy decrease of the system will be less than the entropy increase of the surroundings, and so the entropy of the universe will increase:

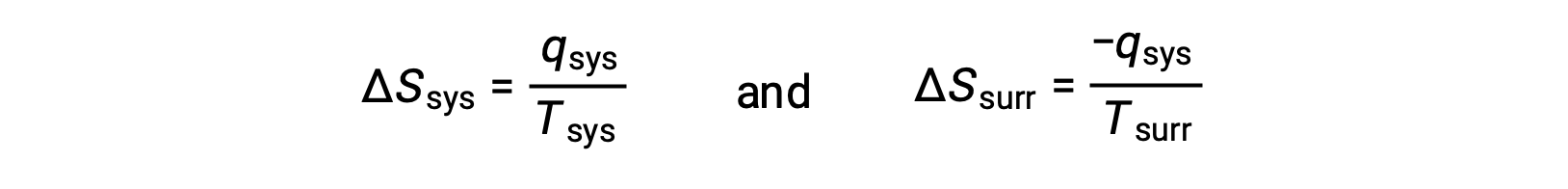

- The objects are at different temperatures, and heat flows from the cooler to the hotter object. This is never observed to occur spontaneously. Again designating the hotter object as the system and invoking the definition of entropy yields the following:

arithmetic signs of qsys denote the gain of heat by the system and the loss of heat by the surroundings. The magnitude of the entropy change for the surroundings will again be greater than that for the system, but in this case, the signs of the heat changes (that is, the direction of the heat flow) will yield a negative value for ΔSuniv. This process involves a decrease in the entropy of the universe.

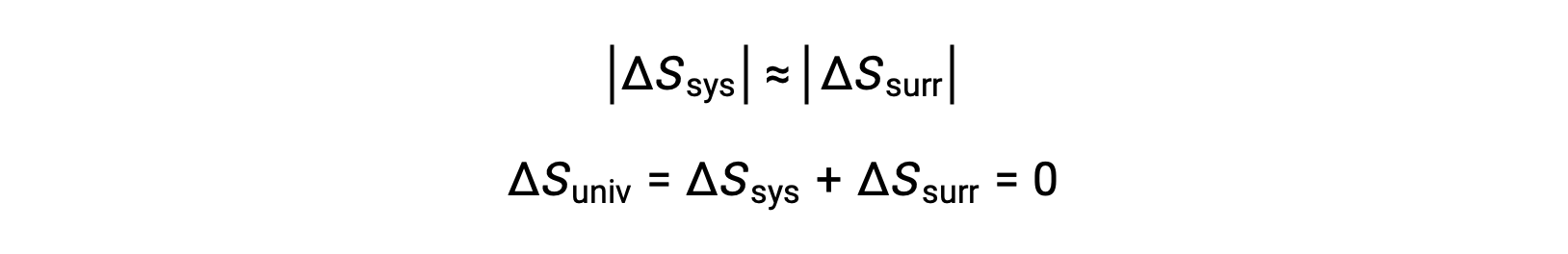

- The objects are at essentially the same temperature, Tsys ≈ Tsurr, and so the magnitudes of the entropy changes are essentially the same for both the system and the surroundings. In this case, the entropy change of the universe is zero, and the system is at equilibrium.

These results lead to a profound statement regarding the relation between entropy and spontaneity known as the second law of thermodynamics: all spontaneous changes cause an increase in the entropy of the universe. A summary of these three relations is provided in the table below.

| The Second Law of Thermodynamics | |

| ΔSuniv > 0 | spontaneous |

| ΔSuniv < 0 | nonspontaneous (spontaneous in opposite direction) |

| ΔSuniv = 0 | at equilibrium |

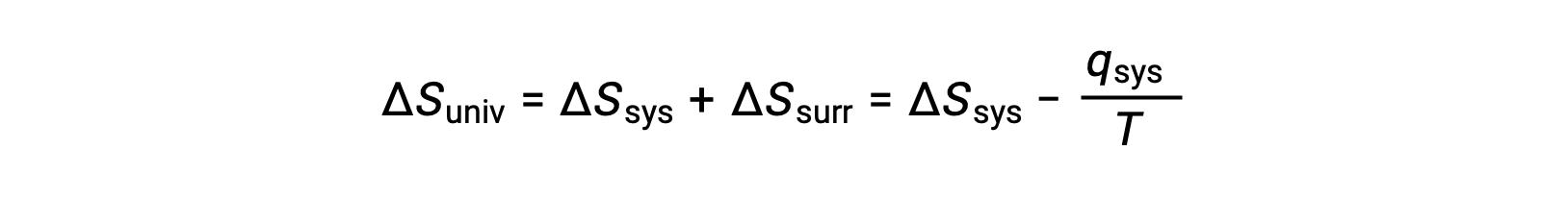

For many realistic applications, the surroundings are vast in comparison to the system. In such cases, the heat gained or lost by the surroundings as a result of some process represents a very small, nearly infinitesimal, fraction of its total thermal energy. For example, combustion of a fuel in air involves transfer of heat from a system (the fuel and oxygen molecules undergoing reaction) to surroundings that are infinitely more massive (the earth’s atmosphere). As a result, qsurr is a good approximation of qsys, and the second law may be stated as the following:

This equation is useful to predict the spontaneity of a process.

This text is adapted from Openstax, Chemistry 2e, Chapter 16.2: The Second and Third Law of Thermodynamics.

Procedure

According to the first law of thermodynamics, the energy change in a system is equal and opposite to the energy change of the surroundings.

When an ice cube, the system, is added to a cup of hot tea, the surroundings, the ice melts while the tea becomes cooler. The heat gained by the ice cube is equal to the heat lost from the tea. Energy is conserved no matter the direction of heat transfer.

However, adding an ice cube would never make the tea hotter because the amount of heat transferred does not determine which way the heat flows.

The associated change in entropy must be considered to explain the direction of heat transfer and other spontaneous reactions.

The second law of thermodynamics states that the entropy of the universe, which is the total entropy of both the system and surroundings, increases for all spontaneous processes. This means that the ΔS of the universe, the difference between the entropy of the universe’s final and initial states, must be greater than zero.

As entropy is a measure of energy dispersal, a process where the energy of the universe is more dispersed in the final state than in the initial will be spontaneous.

When an ice cube melts, the water molecules change from an ordered solid to a more disordered liquid state with a positive change in the entropy of the system; when water freezes into ice, the ΔS of the system is negative.

However, for these processes to be spontaneous, the entropy of the universe must increase, so the difference between whether these processes are spontaneous must be in the surroundings.

When water freezes, it releases heat to the surroundings, increasing the energy dispersal of the surroundings. The ΔS of the surroundings must be positive and greater in magnitude than the ΔS of the system for the ΔS of the universe to be positive.

Pure water will only freeze spontaneously at temperatures below 0 °C. This is because the heat transferred to the surroundings at low temperatures will result in a greater change in entropy than the same heat transferred at higher temperatures.

The magnitude of ΔS of the surroundings is directly proportional to the heat transferred by the system and inversely proportional to the temperature T.

Thus, for any process occurring at a constant temperature and pressure, the ΔS of the surroundings is equal to the heat transferred to the surroundings, divided by the temperature in kelvin.